The listed books are available, some from different sources and Kinnebrew Studios Publishing.

For orders or additional information:

Contact KINNEBREW STUDIO PUBLISHING

siristruble@gmail.com

(269) 967-3241

HUCKLEBERRY MOUNTAIN

33 MILBURN LANE

HENDERSONVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA 28792

return link to book main page

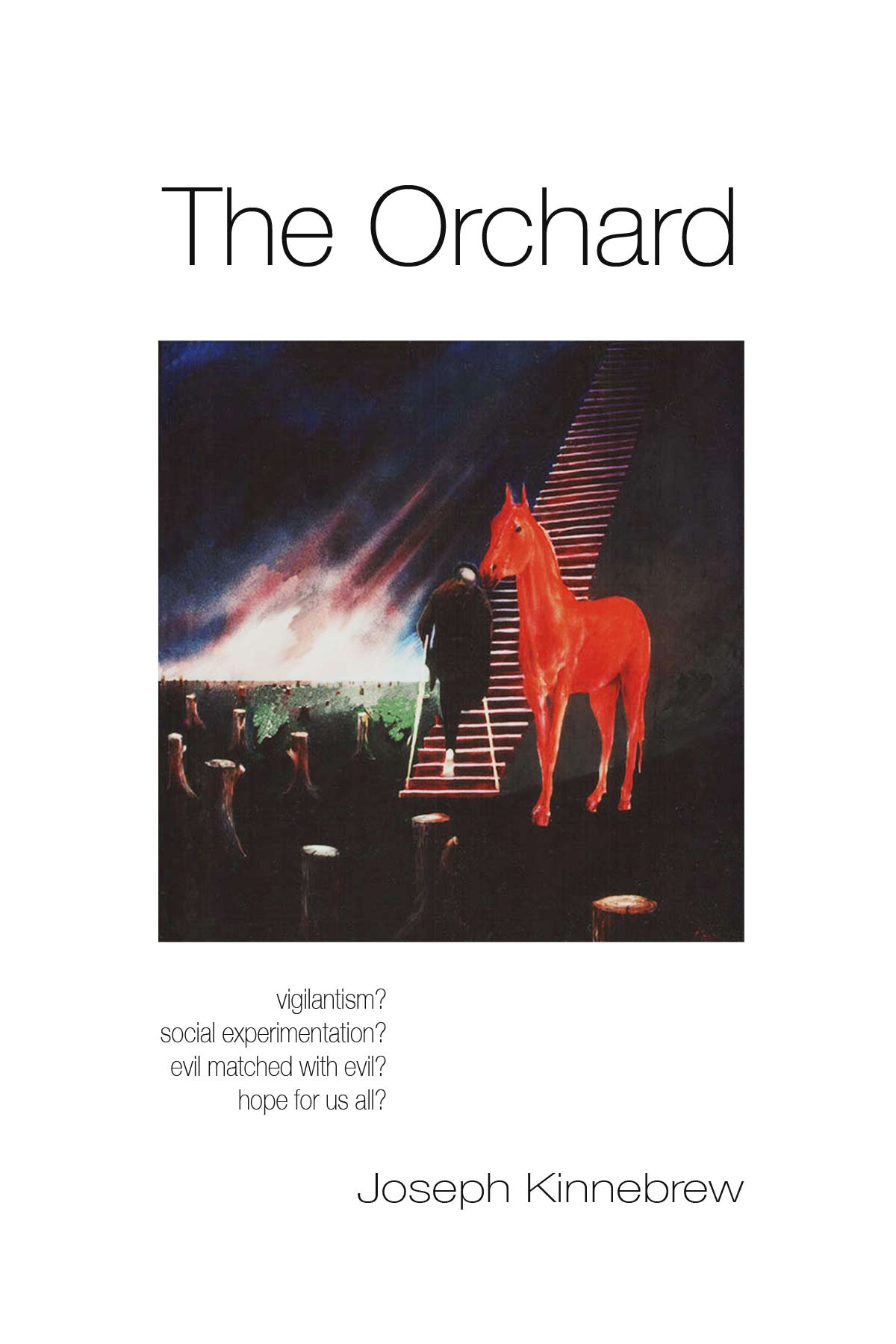

THE ORCHARD

Published by Bookside Press

$17.99

ABOUT

Is it vigilantism?

Is it social experimentation?

Is it evil matched with evil?

Is it about hope for us all?

Is it about a white straight back kitchen chair?

Four legs of faith, forgiveness, redemption and resurrection

A book club

________________________________

Faith

A shared dream

A perpetrator

A psalm to remind

An experiment

________________________________

An opportunity

Forgiveness

___________________________________

A final gift

Redemption

___________________________________

A new journey

Resurrection

________________________________

READER COMMENTS:

READER COMMENTS:

This is a profound book. and not for the faint of heart. Joseph Kinnebrew is a deep thinker and has created a masterpiece for moral debate and further consideration. Kinnebrew crafted a surreal tale using metaphors woven together as only a consummate artist can. This book and ideas of the four concepts of faith, forgiveness, redemption and resurrection of will remain in my mind for some time to come.

Others would do well to read this very important book.

Rear Admiral Edward J. Hogan, USN (ret.)

___________________________________________

I have never fallen so deep into a fiction book which mirrors reality to the extent that I highlighted passages, both large and small. I want to write an Amazon review by the end of the day, but I want to do it right so that those who read my review will want to read it.

Honestly I am still shaken as to where your words took me places so dark unexpected truths were revealed naked and for all to see. I have to admit, I could only read bits at a time just so I could process the gifts of honesty and the consequence (be it even metaphorical) of lying and corruption. Always in the end there is the VOICE, the voice of conscious, of reason, of corruption. !!!

The Orchard is not a book that will be placed on my mental library, not a book to be forgotten after a month or year has passed. This is a book that is now a part of my very existence. How many books can you say with grace, that honestly hold that place? That place of Change.

Joseph, I knew you were an artist with your mind, in cresting all you have visually. But, friend, your writing is an art unto its own.

I should get on now. I am going to go over all my highlights of The Orchard, and write one hell of a review. I have a great format of precise writing when it comes to reviews for Amazon. Your book however deserves five stars+ .

So much to take in.

Would it be strange to say that the last part was my favorite part? The character had to be taken apart almost to the bare bones physically, before he could mentally and spiritually SEE. But not only did he See, he gave back as best he could. I cried at the end. I cried because the end was the beginning of life, as Zo and Azza parted ways so long before. I realized at last the character who had taken so much from others finally gave himself to Everything. I felt the ending brought the whole story completion. It would be hard for others to understand, for those who could only see the physical.

Antonella Novi

__________________________________

The author is a well-known surrealist painter so no surprise, this book is quite surreal. Metaphor, metaphor, metaphor everywhere you turn in this captivating story there are nuances beyond nuances.

Kinnebrew has spun a web of outrage, horror, forgiveness and salvation with characters and themes that seem eternal. This is not a book that pulls its punches. It kept me up nights but also interrupted daytime thoughts as I read the news and pass others on the street. The book poses serious questions and at least for me met its objective as I rethink what we do with those who break the conventions of society. The treatment is harsh but here the result redemptive and touches the soul.

In spite of it all the author seems optimistic about our future and our ability to forgive and be forgiven albeit in very unconventional ways. This drama, its message and outcome will stay with readers for some time… I can’t get it out of my mind and probably never will.

B. Deutsch

______________________________________

Use these links to view individual books

Fiction

little boys, big dreams & the hobo wars

_______________________

Nonfiction

________________________

Art Books

Kinnebrew Retrospective Catalogue

The listed books are available, some from different sources and Kinnebrew Studios Publishing.

For orders or additional information:

Contact KINNEBREW STUDIO PUBLISHING

siristruble@gmail.com

(269) 967-3241

HUCKLEBERRY MOUNTAIN

33 MILBURN LANE

HENDERSONVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA 28792

Exerpts:

1

My name is Cedric Childs, I am a surgeon. I am sixty-eight years old, have been divorced for two years but separated longer and was, last week, diagnosed as having Alzheimer’s Disease. I am a man who plans for the future. I spent most of this week completing the admission forms and making the necessary arrangements to provide for my future care. I started, last August, to reduce my patient load as I have suspected for sometime that the diagnosis of progressive dementia would confirm the symptoms I thought I recognized early last summer. Today is Sunday, December twenty-fourth, Christmas Eve Day. Merry Christmas.

I am alone this evening, in my study, as I have been on Christmas Eve for the past five years. My wife lives in a distant city near her sister who is her only living relative. When we divorced, she said she would never remarry. She is a beautiful woman whose outer persona reflects the one within. I love her very much and know she loves me as well. The end of our lives together has been a tragedy of colliding principles and intentions. Not a conflict between the two of us but rather a conflict within our souls, which became so corrosive that it destroyed the formerly peaceful life we enjoyed. If there is any grace remaining in this I think that in many respects we are like war casualties who believe we have sacrificed ourselves for a higher motive so that others might not pay a similar price. I will not tell her about last week’s diagnosis because it will bring her great pain and I have already shared in bringing a burden upon her which is more than any caring human should do to another. This is a matter of long standing and the complexities of it prompt me in part to at last begin chronicling the events of a small group of people with whom I have been associated for many years.

I have, for some time, contemplated what I would do if this sentence of progressive mental incapacity and blurred vision of the world were pronounced on me. I have thought of suicide by many different means, which would, for the living and those who must live with the consequence of my physical death, be considered natural. I am aware that the taking of ones own life can be a shattering experience to others and how haunting a legacy it would be. So alas, I will do what I must. I will live life to the end and die by the natural causes that are, I suspect, by a slim margin, my obligation as payment for the random gift of life itself. I would wish, perhaps in vein, that at the end of my illness I might be granted a moment of grace, a momentary lapse into unfettered coherent thought. Perhaps I would then again see the world with sad but clear and faintly optimistic eyes. I might remember what this life was about and gain some greater insight into our various preparations for what is next. This notwithstanding, death does not frighten me and madness may be a merciful alternative to the endless debate that now rages inside my brain, my soul and my heart. I am either the devil incarnate or a saint; I do not know which. I have kept the company of conspirators who would challenge many things people in our society have come to know as dear and precious. With my death in sight I now see myself as reduced to the contemplation of my life.

I am a well-educated man and know Earth has been damaged by numerous catastrophes. Some have been the fault of humans but Earth has always proven itself the greater and more enduring presence. Nature itself is not flawless and its errors of process abound as well as its successes. Life is, after all, a serendipitous miracle that has had many forms but few other than bacteria that survived for any great length of time. In the laboratory, under the magnifying lens, I have often seen life joined and then disappear. The miracle and uniqueness of human intelligence does not, in retrospect, seem to be of any particularly great advantage in overcoming the odds for enduring survival. In fact to the contrary, we appear, like other life forms before us to be in danger of causing our own extinction. In spite of this and more frequently now I sometimes think I hear a distant voice. A song from a man sung far back in the comparatively short time of man’s two million years on Earth. It is a sound of thanksgiving and joy. It comforts me. It is a gift. A song that sweeps through me and joins me to others of our kind.

Pathologically my illness will, for a short time, permit me time to write down the events that I have participated in over the past two and half decades, and most particularly the past few years. My journal, now many notebooks, is a reflection of my training. It is the product of both rational observation and artistic interpretation. Medicine after all is still an art. One that reveres precision and consummate skill. Through my own choice and the consent of our group I will chronicle our times together and when I have finished my work will give the manuscript to my old friend, Edwin, who is a painter and himself dwells inordinately on such things as the destiny of human beings. He will, I suspect, not be surprised by what he reads and comes to know about his doctor friend for he knows we all possess many secrets. But I have hidden my, our, secret well. While he will understand Edwin will not necessarily approve of what our group sought to demonstrate, to reaffirm and to suggest as an alternative to our present circumstances in this world. I do not know to whom, other than him, I, or more correctly speaking, we the group as a whole address this journal and the related materials. It is by unanimous agreement and consent, our hope and intention that by providing a record of our motives and the results of our actions we might perhaps be better understood and forgiven if we are judged deranged criminals. I do not believe in heaven but fear a death of eternal damnation. I will begin at the beginning. Not my beginning but with that of our little group. It all seemed so innocent and worthy an undertaking.

2

In the summer of 1969 I received a note from General Jonathan Little who years before had been first a patient and then a friend. Initially I had seen him privately because he had an obscure endocrinology problem and wanted to remain informed about his condition outside the scrutiny of military doctors whose opinions or actions might cause him career path problems. Jonathan was a methodical man who knew well the perils of professional ascendancy and believed that forewarned was forearmed. He had become a two star general and was being posted back to the New York Area where my wife and I have lived ever since I completed my residency at Johns Hopkins. That autumn he would take up his post as an instructor at the military academy north of the city and also be a commuter to Washington DC serving as an advisor to the Pentagon. He had always wanted to return and “live in the heart of New York City,” he wrote, and looked forward to renewing our friendship. He apparently no longer needed me as his outside medical consultant.

When he arrived in the Manhattan my wife, Mary, and I saw him frequently at first and then as the months wore on less so. As Christmas drew near that year we again saw more of Jonathan. Mary and I have no children of our own and enjoyed this holiday season particularly when our friends became like family. Since Jonathan was unmarried and alone we invited him for dinner Christmas Eve. It was twenty-five years ago tonight, 1969, and I mark it in recent years with a sense of irony. The eve of Christ’s birth. The man, who Christians believe, came to save mankind more or less from themselves. The man who brought an offer of forgiveness and redemption through revelation and in return asked us for faith.

Mary prepared a lovely dinner and the three of us talked about many things of mutual interest. Eventually the topic turned to recent books we had all read and I was astonished to discover that Jonathan was widely read and well versed in areas that I would not have imagined for a man whose life had been devoted so completely to his country and the military. He read with enthusiasm and insightful understanding across the fields of philosophy, psychology and geology. I knew that he taught history and evolution of military tactics but I found it fascinating that he was able to weave his other interests back and forth incorporating them into the rich fabric of his history lectures. That’s how it started. Books. The three of us decided to read a book, have dinner again and talk about it.

In early February Jonathan invited us for dinner and a discussion of the book we all had by that time read. It was popular at the time, Theodore Roszak’s, The Making of A Counter Culture. It was about the perils of degrading visionary experience that in turn diminished our own more real or actual experience in contemporary life. In 1969 it had been out a year. It was being discussed primarily by people in colleges and universities on the west and east coasts and was not the kind of subject that military people took to kindly in that era of the Viet Nam War and protest. After completing the book I felt there were some themes that still might appeal to Jonathan and his peers. Roszak wrote about undermanagement, not the reverse, and the failure of technology and playboy permissiveness. The three of us were all in our early forties but on the pages of Roszak’s book we heard the sweet songs of our youth and its accompanying optimistic enthusiasm.

Mary worked in the New York City Department of Social Services as a case reviewer. She dealt primarily with first time adolescent criminal offenders. With Jonathan teaching young soldiers who would be our future military leaders and me seeing young doctors whose rounds I scheduled and comments I reviewed, we all related to the young, active student culture of the waning turbulent sixties. We felt a part of it and were sympathetic to many of the questions and challenges being posed to the country by its youthful inheritors. Jonathan was surprisingly tolerant of the anti-war demonstrations and liberal in his views of free speech. But he was equally intolerant of those who would not use the precious inheritance of freedom to come to terms with racial bias, greed, and corruption. He was also easily angered about injustice, social and criminal. General Little was a complicated soldier, the kind of man who, if we had to have men of war we would want behind the trigger. He was a man of conscience.

To our delight, Mary, Jonathan and I discussed the book sitting cross-legged in an exquisite Japanese restaurant in midtown Manhattan where the General was an obvious regular. He had reserved a private shoji screened room and arranged for an unusual ten-course dinner. As each course was presented in the exquisite minimalist fashion of delicate diminutive portions it seemed that the setting, the exotic food, and the subject of the book all worked in concert to bring us to provocative insights of the society and culture of the late sixties. I even forgot how cramped my legs felt. Mary finally turned and with her back rested against my side stretched her legs out and ate sidesaddle while we talked. The attractive and gracious kimono clad young woman who served us showed no expression of disapproval.

America, Roszak said, was waking up to find the enemy not in its factories, on the battlefield, or in the office. The enemy of American society was “across the breakfast table in the person of its own pampered children.” The children would win, as they usually did with the passage of time and their own evolving maturity.

“The young, miserably educated as they are, bring with them almost nothing but healthy instincts. The project of building a sophisticated framework of thought atop those instincts is rather like trying to graft an oak tree upon a wildflower. How to sustain the oak tree? More important how to avoid crushing the wildflowers. Theodore Roszak

I reflect on these words from time to time. I keep that first book of our discussion close at hand as a more than sentimental memento of what we were to become, together.